Meeting Mister Pinzgauer

Note: if you are reading this on a mobile device you may have to view the article in landscape in order for image gallery captions to display.

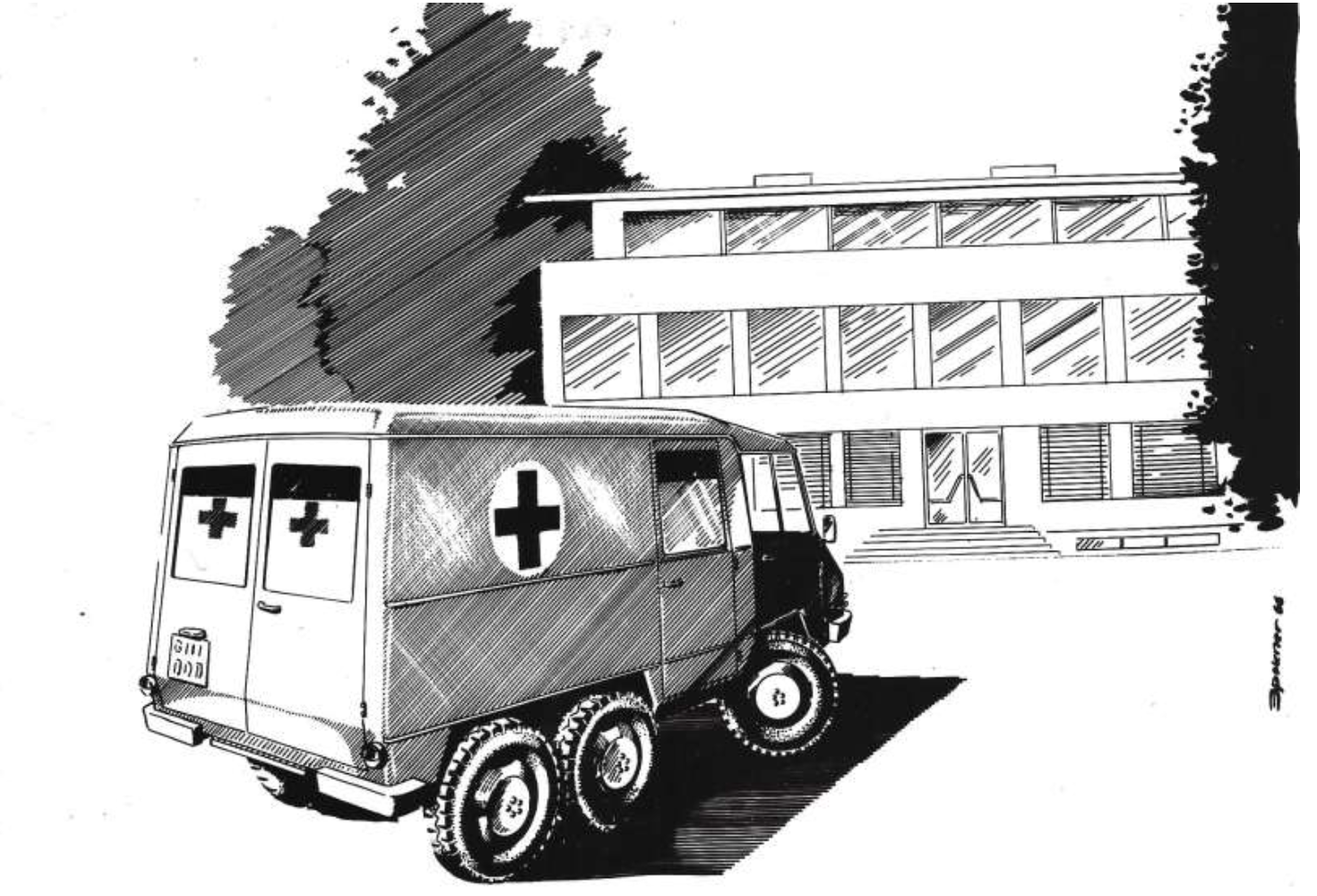

Let’s begin with a simple question: What is a Pinzgauer? The straight answer would be that it’s a rare Austrian military truck, named after a local horse breed. A much better response, however, would be this: it’s the vehicle you would want to have in your garage when the zombie apocalypse hits – an unstoppable off-roader that can get you through rivers, mountains, deserts and, presumably, hungry hordes of the living dead.

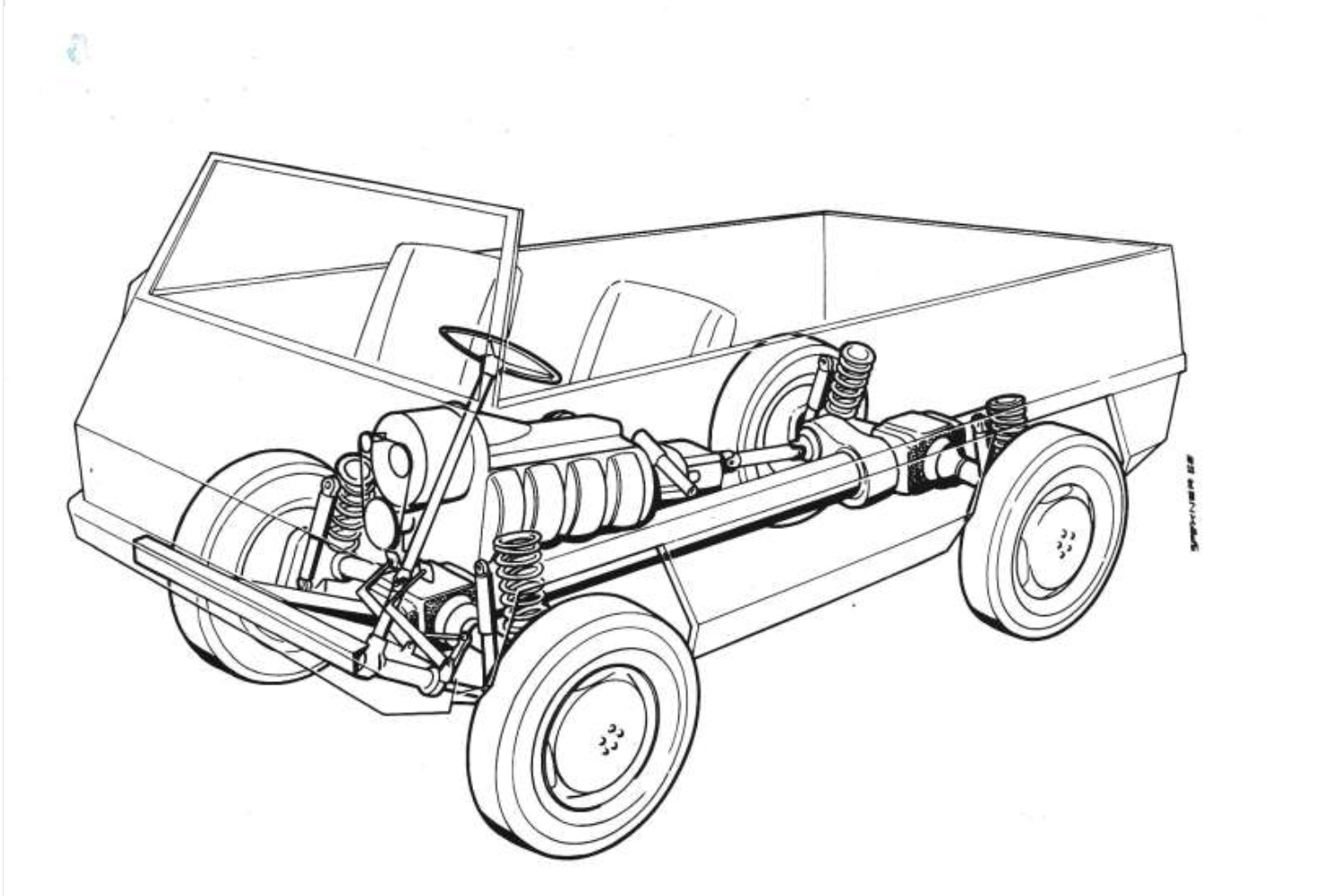

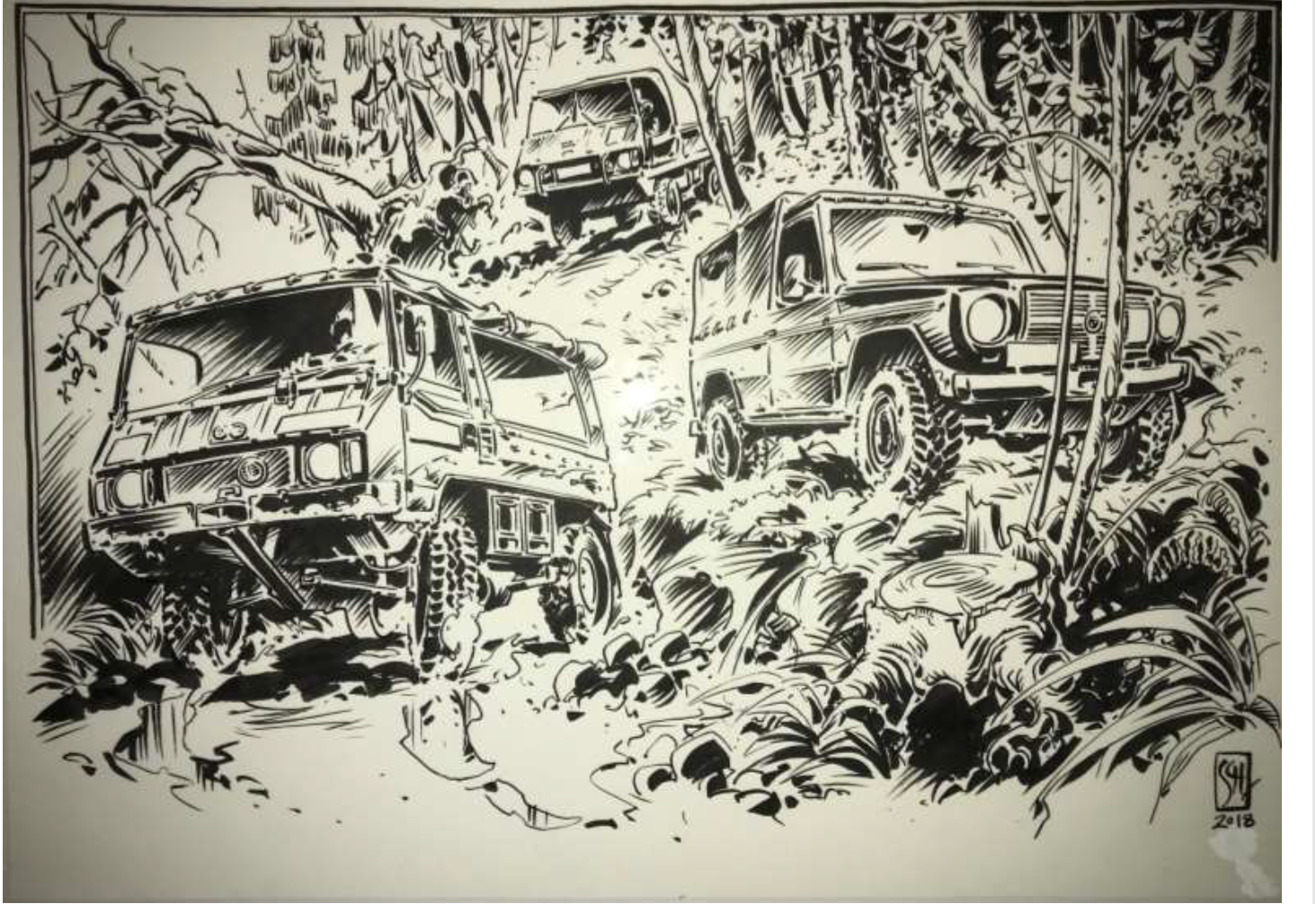

Even among a 4x4 crowd, it can be difficult to convey what an epic off-road ride the Pinzgauer is. A few comparisons, to bring it into perspective: this thing has more ground clearance than a Hummer, a better approach angle than a Jeep Wrangler, more wading depth than a Land Rover Defender and climbing abilities that are simply off the charts. Its portal axles move independently of each other, meaning that as long as the ground is firm, a Pinzgauer can handle inclines even mountain goats might flinch at. Or, as the manufacturer, Steyr-Puch, puts it, “up to the grip limit of the tires”.

Even among the 4x4 crowd, it can be difficult to convey what an epic off-road ride the Pinzgauer is.

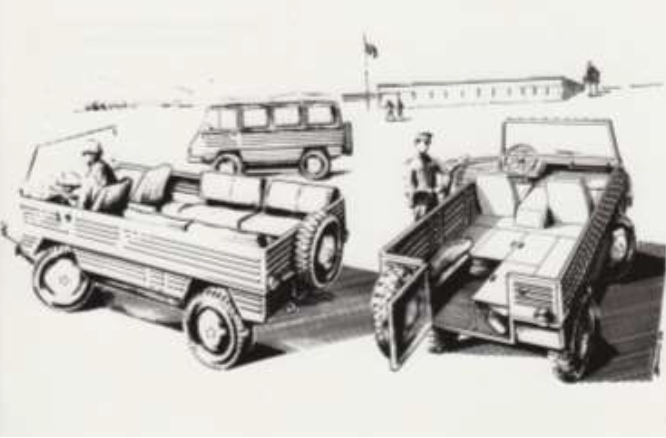

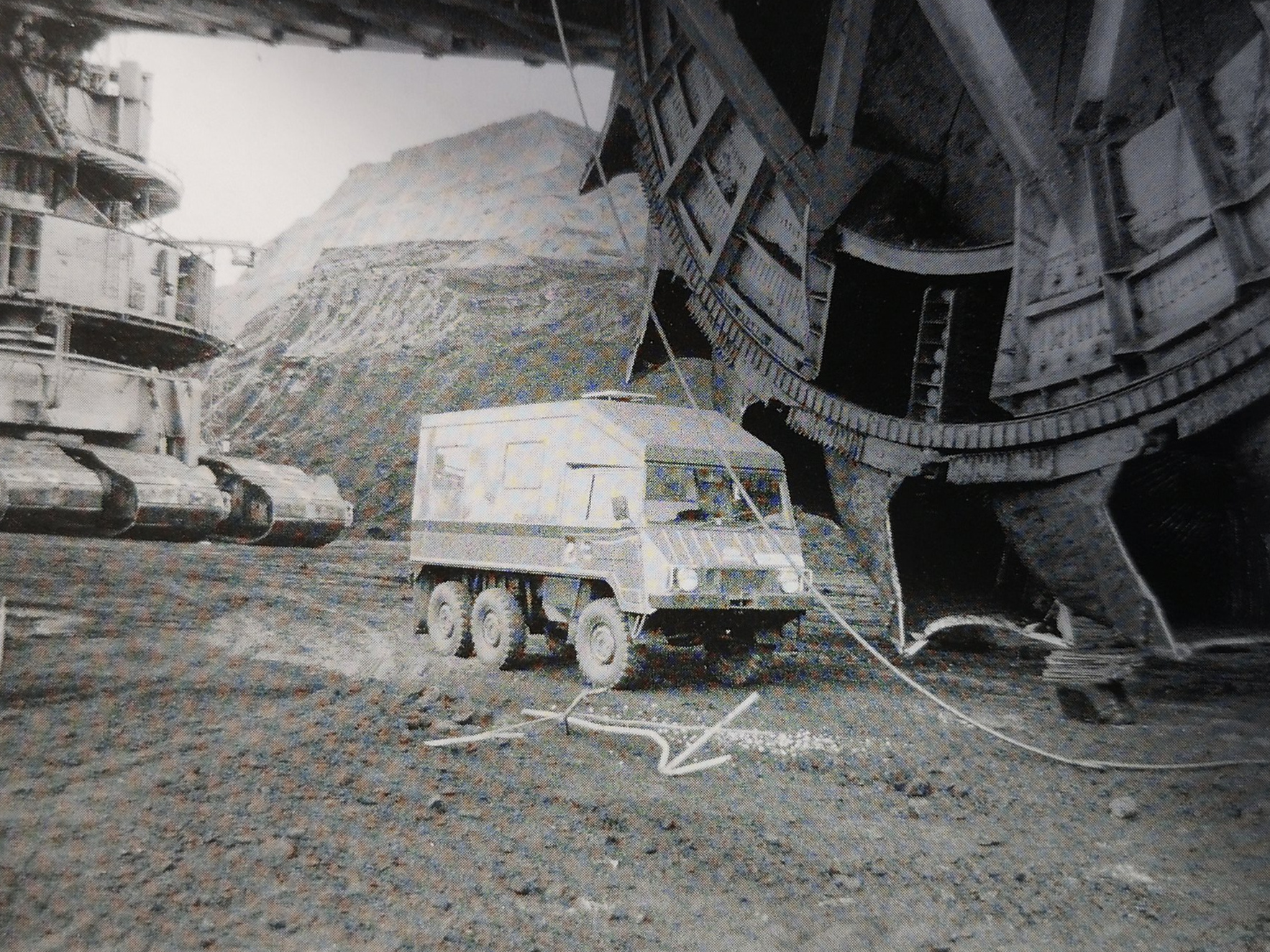

A special edition of the Pinzgauer even featured caterpillar drive. To see more archive images, check out the gallery above.

The Pinzgauer also paved the way for an off-road legend that has kept the Austrian town of Graz in the global automotive game ever since: the Puch G, better known as the Mercedes G Class. Without the success of the Pinzgauer, Daimler-Benz would probably have opted to develop the G-Wagen in-house. That a leading international carmaker teamed up with Steyr-Puch, instead of handing the job to its own engineers, is a testament to the Pinzgauer’s impressive performance in the field.

Between 1967 and 1999, Steyr-Puch built more than 16,000 Pinzgauers, mostly assembled by hand. But the Pinzgauer’s humble origins did not hinder its global success. From the European Alps to the Andes, from the Arctic Circle to the remotest areas of Africa and the Middle East, Pinzgauers were used to move cargo and personnel around terrains previously only served by helicopter or cableway. Some describe it as the Swiss army knife of off-road vehicles.

Today, converted old Pinzgauers, like this one in Oman, are gaining popularity among adventure travellers and off-roaders everywhere. Photo credit: Bassam Al Jabri

These days, the Pinzgauer is enjoying somewhat of a revival. Serious off-roaders and car collectors covet it with cult-like fervor. A classic gasoline Pinz from the 1970s can sell for up to € 50,000 (around US$ 55,000). The later diesel models, especially if they are heavily modified, can go for up to € 100,000 (around US$ 110,000). It is safe to assume that Arnold Schwarzenegger’s highly customised 6x6 diesel Pinzgauer went for even more. Entire Internet forums in Germany, France, Britain and the United States evolve around the Pinz. World travellers and vanlifers have also discovered it as a capable base vehicle for all manner of incredible conversions.

And the kicker? Sourcing spare parts, even for the oldest models, remains easy. Although they are far from cheap, you don’t need to trawl junk yards to find them. Every single part is still in production and readily available online through S-Tec, the local successor of Puch as well as a variety of international suppliers.

Entire Internet forums in Germany, France, Britain and the United States evolve around the Pinzgauer. World travellers and vanlifers have also discovered it as a capable base vehicle.

Why am I telling you all this? Because it may help to explain my excitement when I recently had the chance to meet Dr Egon Rudolf, also known as ‘Mister Pinzgauer’. He was one of its inventors, a man who spent his entire working life in the service of the Austrian carmaker Steyr-Puch. He started out as a graduate at the company’s manufacturing plant in Graz, in 1955, and retired as its director, in 1987. Thanks to an uncanny coincidence of the kind that happens in small towns, I was lucky enough to meet Dr Rudolf in person. Let’s just say, I was more than a little thrilled.

Dr Egon Rudolf and Lisa Reinisch, with an original wooden 3D model of the 1979 ‘civilian version’ of the Pinzgauer, pictured at the Rudolf family home in Graz, Austria.

Rudolf, now in his early 90s, was 27 years old when he joined what was then called the Steyr-Puch AG as a technical engineer. At the time, the company was one of the leading international producers of bicycles as well as a burgeoning car manufacturer. Rudolf, along with other automotive pioneers such as Erich Ledwinka, played leading roles in the golden age of Austrian car making.

A formidable figure and dyed-in-the-wool engineer, Rudolf’s career coincided with turbulent periods of world history: the troubled post-war years, the Cold War and the dawn of the digital age. As the evening progressed, he shared anecdotes from the factory floor, mixed in with memories of state visits and business negotiations in far-flung places.

When Rudolf let on that his wife was the proud owner of an electric car, I knew we just had to talk more. Some time later, the Rudolfs graciously welcomed me at their home for the following interview.

Lisa Reinisch: How did you come to work for Steyr-Puch?

Dr Egon Rudolf: I had just finished my studies at the University of Technology, when I was offered two jobs: one in Germany and one here in Graz. I would have probably moved to Germany if my mentor hadn’t intervened and convinced me to stay. Back then, you have to imagine, lawyers and doctors earned 700 Shillings (approximately US$ 254 today). But as an engineer salaries started at 1,800 or 2,000 Shillings (US$ 655 or US$ 728). For us fresh graduates, filled with perhaps a little too much confidence, it was clear that we wouldn’t stay for anything less than 2,000.

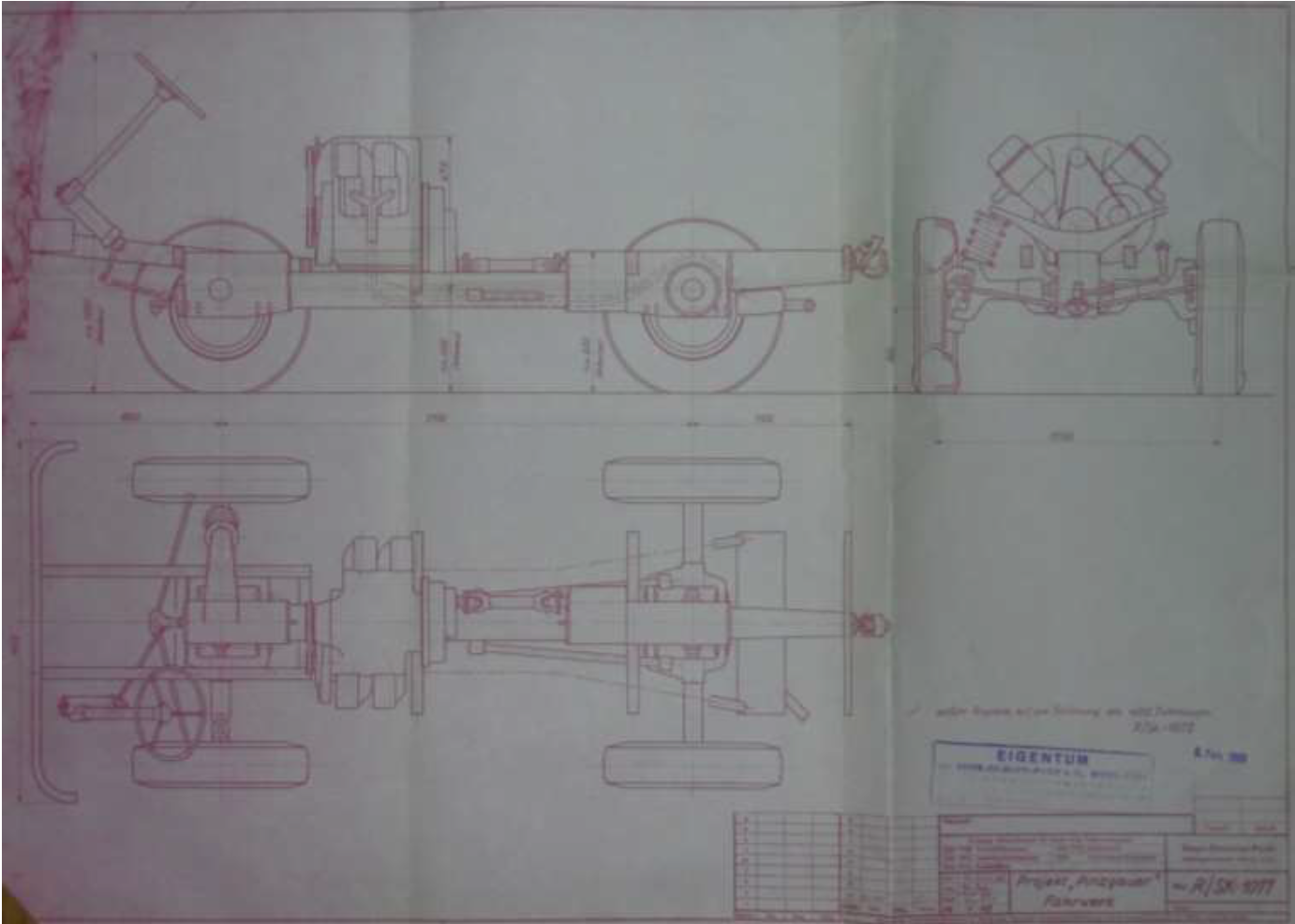

One of the first technical drawings of the Pinzgauer, by Christoph Zeiler (1962).

The start of my career was marked by the difficult decision of the company’s then-director, my predecessor, to focus production on the passenger vehicle segment, namely the Puch 500, and gradually move away from bicycles and motorbikes. At one point, we were the world’s second biggest manufacturer of bicycles, but the demand simply wasn’t there anymore.

To bring about this change, a new team had to be assembled. Partly, this consisted of seasoned constructors from Steyr and, partly, it was junior engineers, fresh graduates like myself. It was this team that tried to sustain the plant. This worked out relatively well, especially in the beginning, since large military contracts were geared towards finding a replacement for the Jeep, meaning a light all-terrain vehicle, agile as a mule – that’s how the name “Haflinger“ first came up. We already had a capable engine, from the Puch 500, which was a new design, as well as a number of other components. Contracts were in the air and that’s how the Haflinger succeeded.

How did the idea for the Pinzgauer come up?

The concept for the Pinzgauer came up in the early 1960s and the first prototype, seen here, was built in 1965.

It was a logical consequence that nobody had intuited back then: after around 16,000 Haflingers sold to various armies, our main clientele at the time, people started looking for a bigger vehicle, especially from reputable brands, such as Mercedes or Fiat. So, after liaising with major merchants, we decided to also give it a go.

The Pinzgauer had a similar life rhythm as the Haflinger. Armies assigned large contracts – up to 7,000 vehicles in the case of the Swiss army. At a time when our factory only had capacity to produce 2,000 per year! We lived off the Pinzgauer for many years. After some years, just as with the Haflinger, the armies had filled their fleets. Meanwhile, organisations using Pinzgauers for civil purposes, such as fire brigades, kept their vehicles in service for 15 to 20 years. So contracts for this type of vehicle were drying up.

At that point, the Pinzgauer became of interest for the private market. Today, when you look at the lists of vehicles being repaired for private use, there are still well over 1,000 registered just on our local roads here. Not bad considering a total quantity of just 16,000.

In 1999, with a heavy heart, we assembled the last Pinzgauer here in Graz. We ended up selling everything off to England, since there were still large contractors and other obligations to consider.

“The swiss army ordered 7,000 vehicles. At a time when we only had the capacity to produce 2,000 A year!

We lived off the Pinzgauer for many years.”

Your career began in the famished post-war era and lasted well into the booming 80s. How does it feel to look back on all that progress, all that change, all that drama?

When you leaf through my book, you will see that it’s the life story of a manager, who spent his whole life at work, always for the same company and in the same industry. Of course, it would be unfair to claim that everything comes down to one person – far from it! As is generally known, success takes time. Even once you make it to the top of a company, you may be able to dictate some things but every executive has ideas, as does every manager and every employee, it’s not that simple. Monikers like “father of four-wheel drive technology”, for example, certainly don’t apply, because there were always several companies and individuals working on things in parallel at any given time.

We were a motley crew – but in a good way. From the beginning, there was resentment between the car engineers from Steyr and the bicycle engineers from Puch. Both eyed each other somewhat suspiciously. It was a challenge to unite these very different people, some of which were at the top of their game.

Dr Egon Rudolf (standing, third from right) and his team during a trial on Zirbitzkogel Mountain, 1960.

“We were a motley crew – but in a good way.”

Take the chassis constructor, Erwin Musger. He had previously constructed gliders. The head of our department was a former weapons constructor for the Steyr arms factory – again no automotive background. We were all very different, some of us straight from university and convinced that we knew everything. But, as it turned out, that was not the case.

Once, the head of our department, an old constructor who was up to every trick, asked me to design an expansion screw. Internally, I revolted and thought to myself: “An expansion screw? Really?” But there was no discussion, so I, full of theoretical knowledge, set about designing the screw as I had done at university. After about two days, he came over to observe my miracle – rendered, of course, without a computer, just with a simple drawing board – in three-dimensions, though the third dimension was only in one’s brain back then. Never mind a fourth one! Anyways, he came over and informed me that this screw may well work in theory but would clearly break and not expand as required in real life. I learned a lot from that man.

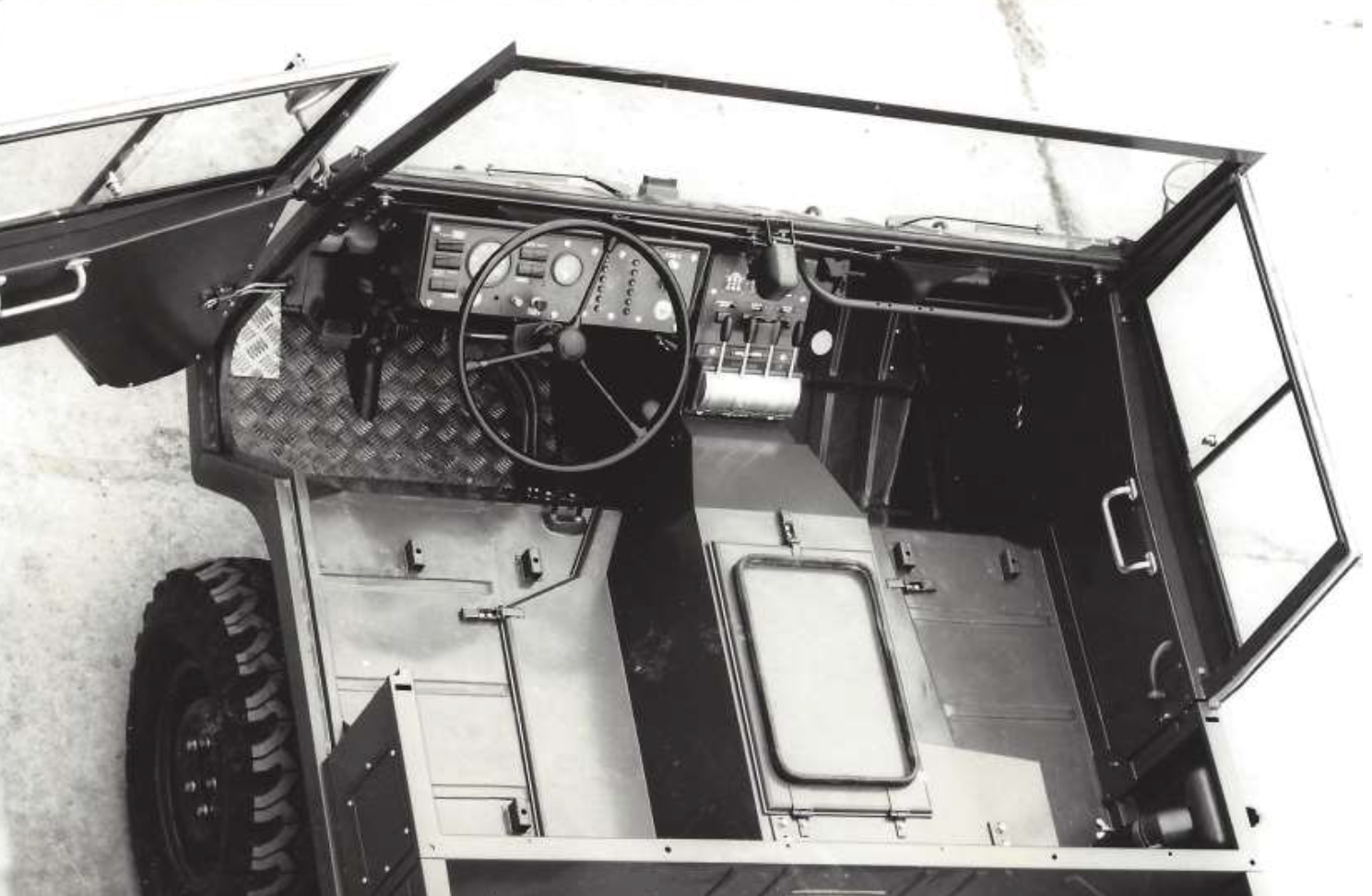

From today’s perspective, it is difficult to imagine how it was even possible to build cars with the tools and methods available back then; hand-drawn blueprints, wooden models, mechanical calculators. Steyr-Puch vehicles were assembled by hand well into the 1970s. Do you ever get nostalgic about those days?

It’s a different world now. And this different world has a vent, which is the price tag – along with customers who don’t want to pay more and want things they’ll probably never need. Just ask yourself whether you really need the proximity sensor that comes with your car – what for? And what about cigarette lighters? Smoking inside a car isn’t even allowed and yet, they are everywhere. Who needs all that?

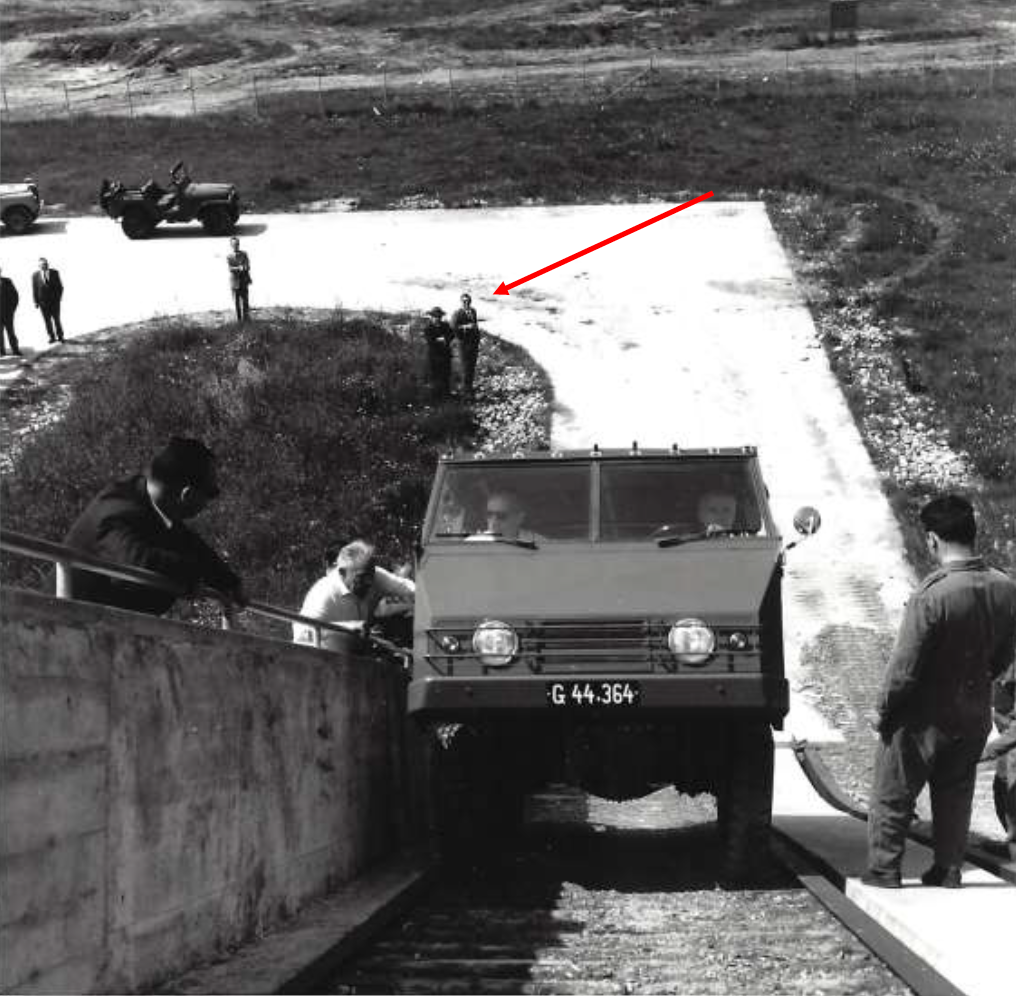

What is it about the Pinzgauer that made it stick out from the competition?

Swedish, Swiss and Austrian military officials on the back of a Pinzgauer during a trial north of the Arctic Circle, where the pre-production vehicle performed well at temperatures of -35 and -40 degrees Celsius (1968).

It’s the kind of vehicles, like the Unimog, which you can fix yourself, even if you break down in the middle of the desert somewhere. As long as you have the right tools and halfway know how everything works, you can do repairs in a way you couldn’t in a contemporary car. That’s the key advantage of these vehicles and it was a necessity for many of our major customers.

These vehicles – Puch 500, Haflinger, Pinzgauer and Puch G – became popular with globetrotters. You have to imagine, there were people who traversed the Sahara in them. People who held elevation records after taking them to 6,000 metres in the Andes, no problem. In many cases, we provided training for them beforehand – some turned out better than others but they all achieved a certain level of competence. The fact is, in some countries you can cross hundreds of kilometres without coming across a gas station or anyone who even has a wrench. These are the situations where these cars excel to this day.

Steyr-Puch was known for its thorough field trials, often in harsh environments and in direct competition with other carmakers. Can you tell us about some of the toughest trials you experienced?

In 1973, this Pinzgauer crossed the Sahara desert, without needing any major repairs.

I wasn’t there for the whole trip but once we drove two Pinzgauers all the way from Gibraltar to Lagos, crossing the entire Sahara. After we arrived, we presented them to the military leadership there and the cars were a little dusty, but that’s it. They asked us about our arrangements on the cargo ship, whether the vehicles had been stowed above or below deck. That’s when we told them that we’d just come through the Sahara, via Morocco.

They were air-cooled racing models. On a trip of over 8,000 kilometres, they didn’t have any issues, except one or two tyre changes. Overall, they logged averages of between 60 km/h and 80 km/h, which is a lot considering the route and that the maximum speed is only between 100 and 110 km/h.

In the Andes, the local generals were surprised that I drove the vehicle up there myself. We had hardly any problems, even when driving above 5,000 metres. A few years later, when we already had the fuel injection engine, we went up there again and people expected the engines to require readjustments, but by no means! We drove on the same settings from zero to 5,000 metres.

At almost 5,000 metres, in the Peruvian Andes, the Pinzgauer proved it could also handle extreme altitudes without a hitch (1982).

“In the Andes, the local generals were surprised that I drove the vehicle up there myself.”

Our colleagues at Mercedes always said they didn’t care for the Pinzgauer, that we weren’t good constructors. So we said, alright, let’s put this to the test. When we arrived at their testing grounds in Gaggenau with a Pinzgauer and a Haflinger, they laughed because the area was graded in a way that was just doable for the Unimog, certainly not for a tiny Haflinger.

When the demonstration began, everyone was pretty tense, including both company chairmen. First, it was the Unimog, which just about managed to get its wheels over the threshholds. Afterwards, one of the Mercedes guys, their head of R&D at the time, came over to us and said, “I guess you’ll have to carry the Haflinger up there.”

Then we released the Pinzgauer, which easily managed the track. The only thing was that the front axle, which was lower than the threshold, needed to go over but our driver overcame that quite well with a bit of rocking. That’s when the other team became a little more subdued.

Next, it was time for the Haflinger. That was the point when I thought to myself, this will be the biggest disgrace. And in front of the assembled general management! But they drove the Haflinger just like the others, despite the smaller tyres and slope angle. And, somehow, the vehicle pushed itself up the inclines. I have to say, our colleagues at Daimler were fair and admitted that they hadn’t thought this was going to be possible.

“Our colleagues at Daimler were fair and admitted that they hadn’t thought this was going to be possible.”

The ‘civilian’ Pinzgauer never really took off in the United States despite positive media coverage such as this.

Did you ever have issues with industrial espionage?

Interestingly, when it comes to the Pinzgauer, we didn’t have problems with secrecy. It was different with the G, where journalists would wait en-route to our testing grounds on Schöckl Mountain, but I wouldn’t call that industrial espionage. Anyone who wanted to access our computers would have needed my signature as well as that of our head of R&D, I doubt anyone would have gone to those lengths.

Once we did have an interesting experience during a weeklong trial run in Sweden. We were all staying at a hotel north of the Arctic Circle – us, the Volvo people, the Swedish military attaché and the Austrian military attaché. Afterwards, when we were back in Stockholm to prepare our departure, there was a lot of commotion because the Pinzgauer had suddenly disappeared. The container was empty. The Swedish representatives there were incredibly embarrassed and immediately launched a search. A day later, the vehicle reappeared. It wasn’t damaged but it was clear it had been put through the paces by an expert driver. It looked as though someone had wanted to see how far the vehicle could be pushed. Admittedly, our people had left the container unlocked, which was more than a little careless.

Austria is a neutral country with a strong pacifist movement. How did this affect sales and distribution of the Pinzgauer?

There were circles that tried to block whole productions, who used all possible means to prevent shipments, especially to conflict areas. We always maintained that the Pinzgauer is not a weapon. Of course, it can be used as an arms carrier, but that wasn’t our doing. The argument was always that it’s a troop carrier. Which isn’t exactly true, since the minute some armies got a hold of the vehicles, they added all sorts of rockets and anything you could cram onto the back. It’s a legal formality but I always carried a ministerial letter in my briefcase that confirmed our vehicles were not weapons. Nevertheless, the question kept coming up.

Internationally, there were always countries where you had to be careful of the politics. We had a truck assembly in Nigeria. At the same time, there were negotiations and trials in Namibia. That was sensitive. We couldn’t be seen to be doing business there, otherwise we’d have had to close down the plant in Nigeria. At one point, I was the owner of four passports: a diplomatic passport, one to go to Nigeria, another for Namibia and a fourth to cover everywhere else. We travelled a lot. In some instances, we had 30 to 40 vehicles out for trial runs all around the world.

“At one point, I was the owner of four passports: a diplomatic passport, one to go to Nigeria, another for Namibia and a fourth to cover everywhere else.”

What is your take on electric cars?

The climate problem is obviously proven but the solution can’t be a wholesale attack on drivers. That is a political game, because our politicians are out of their depth. The question is: where do we get the electricity? And what materials go into the batteries, who mines them? All of that is a problem.

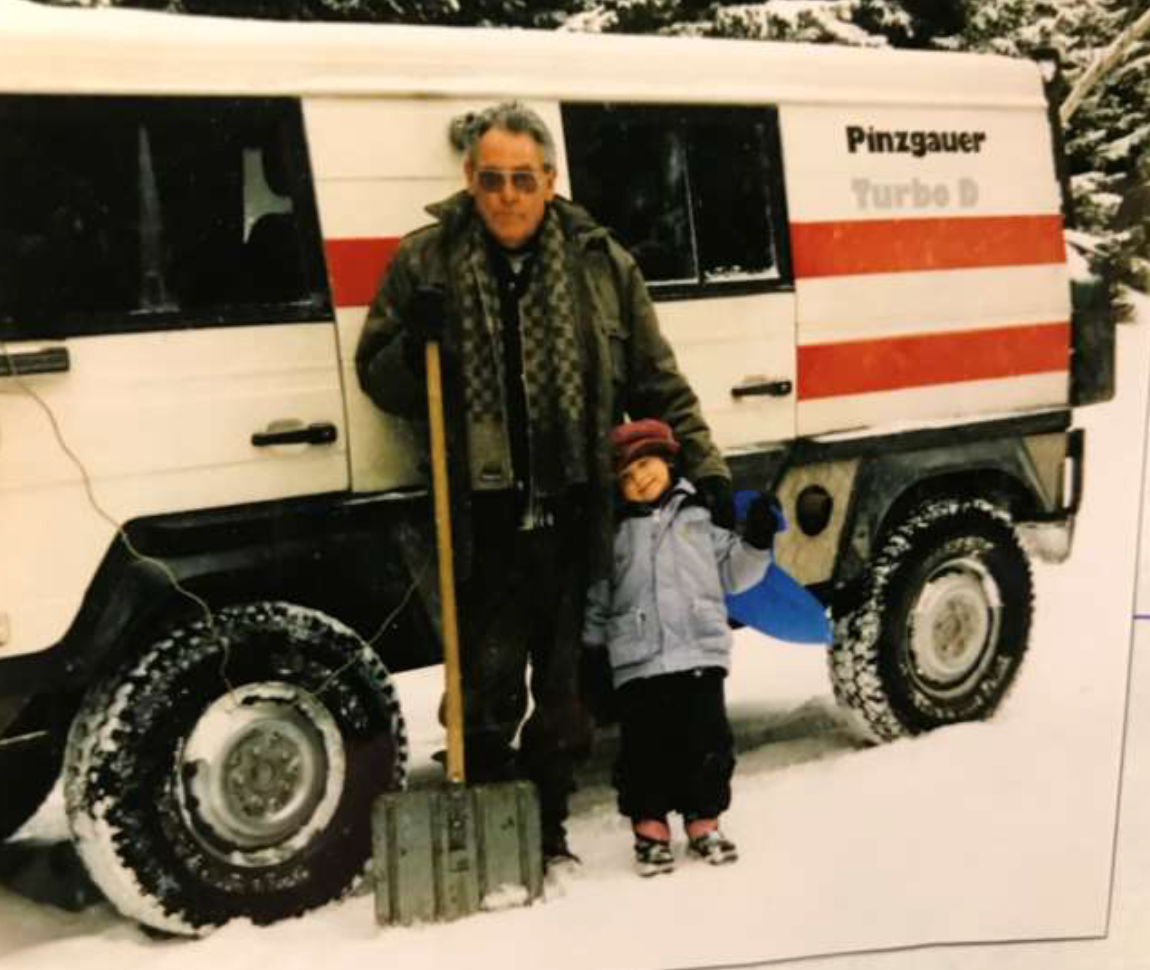

Side bar: after the interview, Rudolf’s son, Markus, gave me a ride home in this beautifully restored Pinzgauer. A true gentleman – like father, like son.

I stopped driving when I was 90, but if I were still active, I’d also get an electric car. And only use a combustion engine to go on holiday. My wife is good at driving Pinzgauers – we have several, after all – but now she prefers her electric car. As you can see outside, however, hers is the only vehicle in our street that drives on electricity.

“I stopped driving when I was 90 but if I were still active, I’d also get an electric car.”

What do you think about Project ECARUS?

Certainly an interesting project. Of course, much depends on your preparations. There’ll be so many electronics; it’ll be impossible to fix things yourself. And with a short range like that, you do have to think about how to go about it. As long as you’re clear on your route and don’t pick the lousiest tracks, like the Rub Al Khali [“Empty Quarter”, Arabian Peninsula], it’s sure to be an interesting project. When I compare it to the trips our clients used to undertake, there’s nothing to be said against it.

From as understated a man as this, we’ll take this as words of encouragement. What a privilege to learn about history from someone who shaped it! The skill, grit and passion that Dr Rudolf and his contemporaries poured into the development of this incredible vehicle are a useful reminder that good things may not come easy but, with a little luck, they can become the stuff of legends.

With special thanks to Markus Rudolf and Gero Dennig, who helped make this encounter possible.